In order to get better at what we do; making the best multimedia student journalism in the state, we need funds to purchase equipment like cameras, and software like the website you're reading this on right now. If you've ever found anything of worth on this website, please consider donating to offset the cost.

Misconduct Increase Poses Concern

More students fall victim to rise in misbehavior post-pandemic

November 9, 2021

The first thing sophomore Joseph Rickher witnessed when walking into the men’s bathroom was the sight of other male students emptying out the menstrual product dispenser, peeling open the products and throwing them onto the ground.

“I didn’t know what to say. I was dumbfounded,” Rickher said. “I felt really uncomfortable … I felt as if I didn’t belong there.”

As a transgender man, Rickher says that this occurrence pushed him to use the gender neutral bathroom even though it’s located all the way adjacent to the nurse’s office on the first floor. He naturally finds it frustrating to make the trip, but not doing so isn’t worth the risk — he doesn’t feel safe using the gendered ones.

This wasn’t the first nor the last case of transphobia Rickher has experienced at Prospect. These instances have occurred not just in the bathrooms, but also the in stairwells and even in classes — where he’ll hear students misgender someone on purpose and face no reaction nor repercussions from the teacher.

Having faced bullying in middle school, Rickher stayed closeted, but he hoped that his peers would dispay more maturity now that they were all coming back to school as high school sophomores — unfortunately, he realized that his expectations were too optimistic.

Having faced bullying in middle school, Rickher stayed closeted, but he hoped that his peers would dispay more maturity now that they were all coming back to school as high school sophomores — unfortunately, he realized that his expectations were too optimistic.

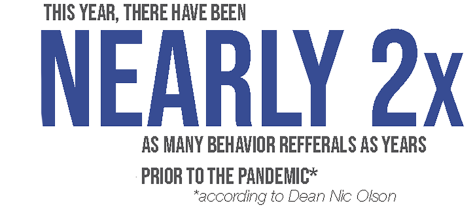

In addition to the transphobic comments and actions, Prospect has seen nearly a 100% increase in behavior referrals this year compared to years pre-pandemic. These behavior referrals include a variety of misdemeanors from parking violations to hate speech. But the referrals that are standing out are those for bullying and vandalism.

In a typical year, freshmen and sophomore males are found to be responsible for most acts of misconduct, however, this school year, there has been a significant rise in those populations’ misbehavior.

This increase drove administration to schedule a 45-minute long assembly on Oct. 19 for each graduating class to address the issue and 25 minutes in school on Oct. 21 dedicated to smaller classroom discussions on the topic.

Principal Greg Minter says that coming back out of remote learning, the faculty and staff were prepared to deal with helping students academically and through mental health struggles. One way they did this was by implementing tutoring groups, but they didn’t predict the impacts of the lack of socialization last school year.

“We’ve never experienced this before,” Minter said. “We’ve never had to have these meetings [addressing behavior to the student body]. We’ve never had these kinds of behaviors [at this level].”

Prospect deans Nicholas Olson and Adam Levinson have already caught about 20 students who vandalized the building. Some even posted videos of their misconduct on TikTok, and Olson said one student told him about how many likes it got and “how good it made him feel.”

Along with positive affirmation from social media, consequences include going through a police investigation for vandalism and theft since it’s a crime chargeable up to a felony and oftens leads to suspension from school. As for using hate speech, the direct consequences can be suspension or even expulsion on top of completing an educational project on why that behavior is wrongful.

While there may be some digital validation promoting certain actions, a number of students at Prospect are disappointed by the rise in misbehavior. The most targeted groups of harassment are transgender students and students of color, according to Minter.

Senior Valeria Navaro* is one of those students of color that has noticed and even been victim to instances of racism on campus. For Navaro, her boots are a symbol of her Mexican culture, and they help bring her closer to her family. With the recent passing of her grandfather, she felt more encouraged to embrace that part of her culture, so she decided to wear her boots to Prospect.

Not long after, she heard a number of people making comments about her shoe choice, asking why she wore them and adding that they were ugly. People she knew even started notifying her that other students were making distasteful comments about her attire.

“I feel like having that … taken away from me … I can’t be myself, and I can’t express myself as a Hispanic,” Navaro said. “I was really hurt when people were talking about my boots ,because they come from Mexico, and I think they’re so beautiful; they helped me feel beautiful. And then hearing negative things said — it hurts.”

Even off campus, it’s a struggle for some students to get home unaffected by other students acting out. Nearly every day, without being a target and solely a bystander, junior Noemi Patyk takes a school bus to go home but is hit by either food or drenched in water being thrown across the bus.

“It’s just really frustrating because after a day at school, you’re tired — you just want to go home, but then [those kids] just start screaming and throwing water everywhere,” Patyk said. “It’s just chaos.”

Patyk remembers having to walk home from the bus stop just for her parents to see her soaked in water. At that point, this activity on the bus was normal, and she decided to email administrators about it along with her enraged parents. The next few days after she reported it, there was a lull in the discord, but the bus resumed to its perpetual waterpark-state a week later even after a number of those students had been suspended, too.

Patyk, Navaro and Rickher were all happy that the assemblies happened and that administration specifically mentioned certain behaviors, but they do fear that not much change will come out of it if it isn’t repeatedly discussed or followed up on.

It wasn’t a surprise to Patyk to hear students laughing about the assemblies either — it just reaffirmed her fear that she may need to start finding a different mode of transportation to school by next month. And for Rickher, he worries that he won’t be able to use the bathroom most convenient for him. For Navaro, she is uncertain that she will be able to display her heritage proudly without receiving negative comments from her peers.

Olson acknowledges that many of the perpetrators don’t realize the magnitude of their actions until they end up in his office to be investigated. At Prospect, depending on the gravity of the violation, a student may face losing the ability to participate in an extracurricular or even expulsion.

One student, Olson recounts, was mortified about the possibility of his coach outside of Prospect hearing about his behavior, knowing that he would barely be able to face the fact that he let down his team.

“For them, the worst part … is the disappointment [from others],” Olson said. “When they’re in here with their family [with] that embarrassment, and they’re crying and feel horrible, you know [they regret it]. Good kids make poor decisions at times, and that’s OK. That’s what we’re here [for] — to help them learn.”

At the assemblies, administrators stressed the importance of notifying the school about misbehavior and have placed QR codes on fliers around the school providing a link to an anonymous tip line. Olson recognizes that it’s difficult to speak up and understands that most bystanders don’t, but he hopes that students realize that it will make a difference.

Navaro is the type of person to stand up for others, and she has in the past, but she does admit that it’s hard sometimes to do so. One time, she was told that she was a “snitch” and a “p*ssy” for using her voice. But in another instance, she saw a freshman boy walking through the cafeteria as other freshmen made him their target to throw food at.

Navaro asked if he was OK, and he said he wasn’t — and that they had been tormenting him since middle school. She went to the deans to report it, but sometimes she passes him in the halls and still sees other students laughing at him.

Even though Navaro may not see immediate resolutions to these situations despite her intervention, she still advocates for herself and others because she doesn’t want to stop trying. Rickher, Patyk and Navaro all know fully well that change doesn’t come easily, but learning to talk about it and help others is the very first step in that process if there is hope for any shift in behavior.

“I just feel like we all shouldn’t be scared to speak up. There’s people that … [know what they are observing is wrong], but they still won’t do anything,” Navaro said. “But .. we should all stick together and take care of one another.”

*name changed for confidentiality