This coming fall, we plan on traveling to the 2025 National High School Journalism Convention in Nashville, Tennessee, where we'll learn from professionals and get better at what we do: making the best multimedia student journalism in the state. If you've ever found anything of worth on this website, please consider donating to offset the cost.

OPINION: Blurred Lines Between Racial Identity

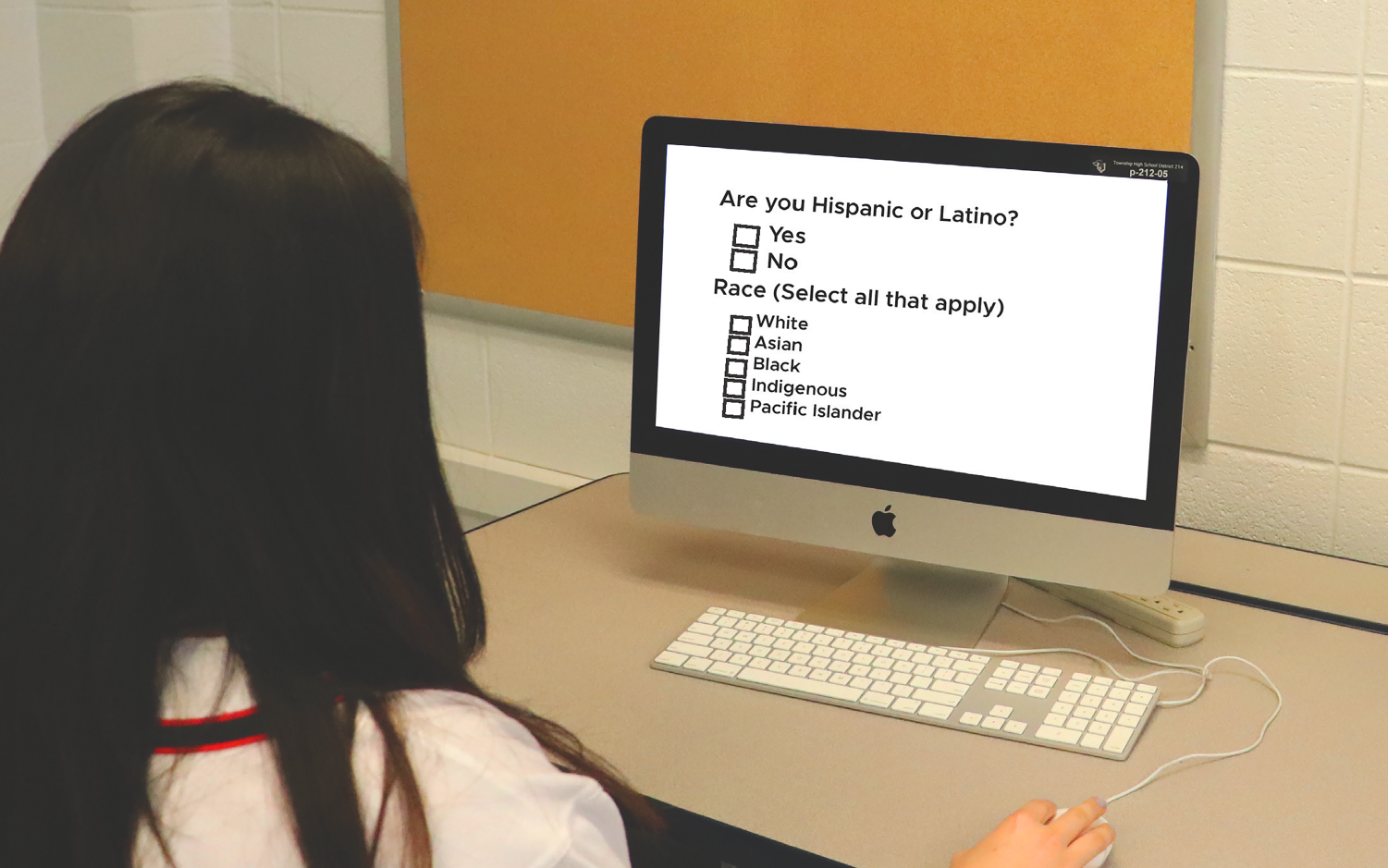

Multiracial teens find difficulty in solidifying their self-perception

April 16, 2021

The first time I was introduced to the concept of race was during preschool in Omaha, Neb., when my peers bullied me for having less eurocentric features and excluded me just on the basis of my looks.

They were constantly questioning me on why I looked the way I did, to which I had no answer. I remember various occasions up through kindergarten where I went crying to my Korean dad telling him that I was done “looking Chinese.”

My dad responded by telling me that I would never look Chinese because I am Korean. But, when my peers were telling me that I was Chinese with such conviction, I was sure they must be right — especially when the concepts of race and ethnicity were so unclear to me at that young age.

Even after my dad told me I was half Korean, I still had questions. Disappointed with my dad’s response, I turned to my white mom with more questions. I asked her, “So if I’m half Korean, which half of me is Korean?”

There were a lot of questions and feelings, most of which lacked clear answers. It seems that even as I grew older and came to understand the definition of terms such as race, ethnicity and ancestry, there are even more gray areas that lead people to argue over what they identify themselves as and what the world perceives them to be.

Racial identity is two fold,; the first being, “How do others perceive me?” and the next is “How do I perceive myself?” This is where it gets complicated because I can’t even count the number of times people have assumed that I was Latina. On more than one occasion in the past year alone, people have exclaimed, “Olivia, are you Mexican?” and “Olivia, I thought you were Hispanic.”

Obviously, I don’t blame them for not knowing because being biracial usually leads to being ethnically ambiguous, and biracial people don’t have just one “look” to them. However, it just makes things more confusing for others and for me when labeling myself.

It’s hard for me to be introspective and even answer that second question: how do you perceive yourself? I, like many mixed people, feel a sense of displacement because to some, I’m too Asian, and to others, I’m not Asian enough. People like President Barack Obama and Duchess of Sussex Meghan Markle, who are both half white and half Black people, have been criticized for not understanding racism in America — essentially describing them as “not Black enough.”

When I was just learning how to count, I also learned to hate my tan skin, my dark hair, my dark eyes and my flat nose. Now, as a junior in high school trying to discover and solidify who I am, I want to be able to proudly claim my Korean heritage, but the disconnect that I worked so hard to enforce as a child is so deeply rooted in the present me.

Whenever I go to a Korean restaurant and try to order a dish in its Korean name, I am not understood by the wait staff because of my heavy American accent. The embarrassment makes my face red, and widens that gap between myself and my Korean identity. When I go back, I order with the English translation so that I don’t look like I’m trying to appear Korean.

It’s easy for me to get frustrated with these labels and to just dismiss them as stupid. I want to tell people that it isn’t important, but it is — especially when you’re growing up and trying to construct your identity as a teen.

According to Act for Youth, “Identity development, the growth of a strong and stable sense of self across a range of identity dimensions, is central to adolescent development.” The process of coming about this identity is one determined by introspection, community, upbringing, family, friends and more, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

As a junior, the time to apply for colleges and scholarships leans near. What I keep being told to share with colleges is what makes me unique and who I am. Not only do colleges want to ask for my race for this uniqueness, but they also want it for admissions.

Scholarships and affirmative action programs can be extremely helpful to those who earn or need them for college,. Many of which are awarded to people of color in an attempt to compensate for a lack of opportunities that arise from systemic racism.

Even in Netflix’s documentary “Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal,” they depict a scene where Rick Singer, the mastermind behind the scheme, tells parents to check the boxes for minority races for their student, even though they don’t identify with those descriptions to gain an advantage in the admissions process.

He was able to do this because, obviously, no one is going to challenge students for being “minority enough.” This scandal is a far extreme of this idea, but this practice does exist on a more casual level.

Some people apply for these scholarships believing they qualify purely based on their genetics;, however, the purpose of those scholarships isn’t really about what is in your blood;, it’s about life experiences. If people choose to identify themselves with good intentions and with honesty, then I wouldn’t be writing this story, but it doesn’t always happen that way.

Still, I’m not even sure if I would have an advantage through affirmative action because even though I have felt hardship because of my race, I don’t believe that I have missed out on as many opportunities as many other people of color have. Even searching “how does being biracial impact college admissions” to include information in this story felt dirty to me.

The first article in my search results said, “Columbia [University] is an institution that supports affirmative action. Because of this, many mixed-race applicants prefer to identify themselves with the most underrepresented minority group on the Common Application.” Just reading this fueled my anger and sadness because people are just trying to play up a system that they might not have ever felt any challenge from while others are genuinely suffering from that same system.

For me, I check off “Asian” and “white” or “multiracial” if I have to. Neither one or the other. But, that’s where my conflict circles back. Am I really Asian? Am I really white? Multiracial is good, but it’s too vague.

Sometimes I feel as if being made fun of for my appearance on the basis of my race in elementary school or even being told that I have coronavirus because of my race just last year is enough to call myself a person of color. But, then I just go back to thinking that that isn’t as bad as what other people might experience like being physically assaulted purely based on their race, so I am lost.

If subjective comparisons aren’t enough for me to build my identity, then maybe looking at numbers would be. The only quantitative data I could have to possibly provide my background is a DNA test. I took one just a few years ago, but it didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already know. However, at the time, I was so excited to take it and receive my results. I just wanted reinforcement of the idea that I really am half white and half Korean.

Further flaws of DNA testing are pointed out by Roots Humanities teacher Michael Andrews; he notes that these programs work by comparing your DNA to others because they can’t just pinpoint exact percentages of your DNA to a location.

He also emphasizes the fact that DNA testing is not the same as genealogy, and that you can’t learn anything about culture from it. However, learning about ancestry can lead to a feeling of connectivity to the human experience, which is the goal of Roots Humanities.

“What I think my students are getting from this is just an overall sense of connectivity [and] feeling of connectivity to look to the larger human family,” Andrews said. “I think you get an incredible sense of perspective, [and feel that] you’re a part of something larger than yourself.”

Another misconception that Andrews sees is that once people find out they have possible ancestors from one area through a genealogy database or DNA testing, they allow themselves to appropriate culture. He specifically referenced an Ancestry commercial where a man does some research and finds out that he is mostly Scottish instead of German like he had thought, he “trades in his lederhosen for a kilt.”

While I don’t often see people picking up traditional clothing of a culture they were not raised with just because a website told them they could, this misconception that DNA is synonymous with culture, family and experiences is harmful.

Because my decision of what to identify as has the potential to have negative consequences, it makes me reluctant to be confident in my choice. I don’t want to consider myself something that I feel that I am not, but like any teenager, I just want to feel that sense of belonging to a group.

I never officially stated what I identify as in this story because I don’t know if me saying that I’m “white” or “Asian” is more than just regurgitation of what my parents clearly are.

My answer to “what race are you” will always have a “but.”