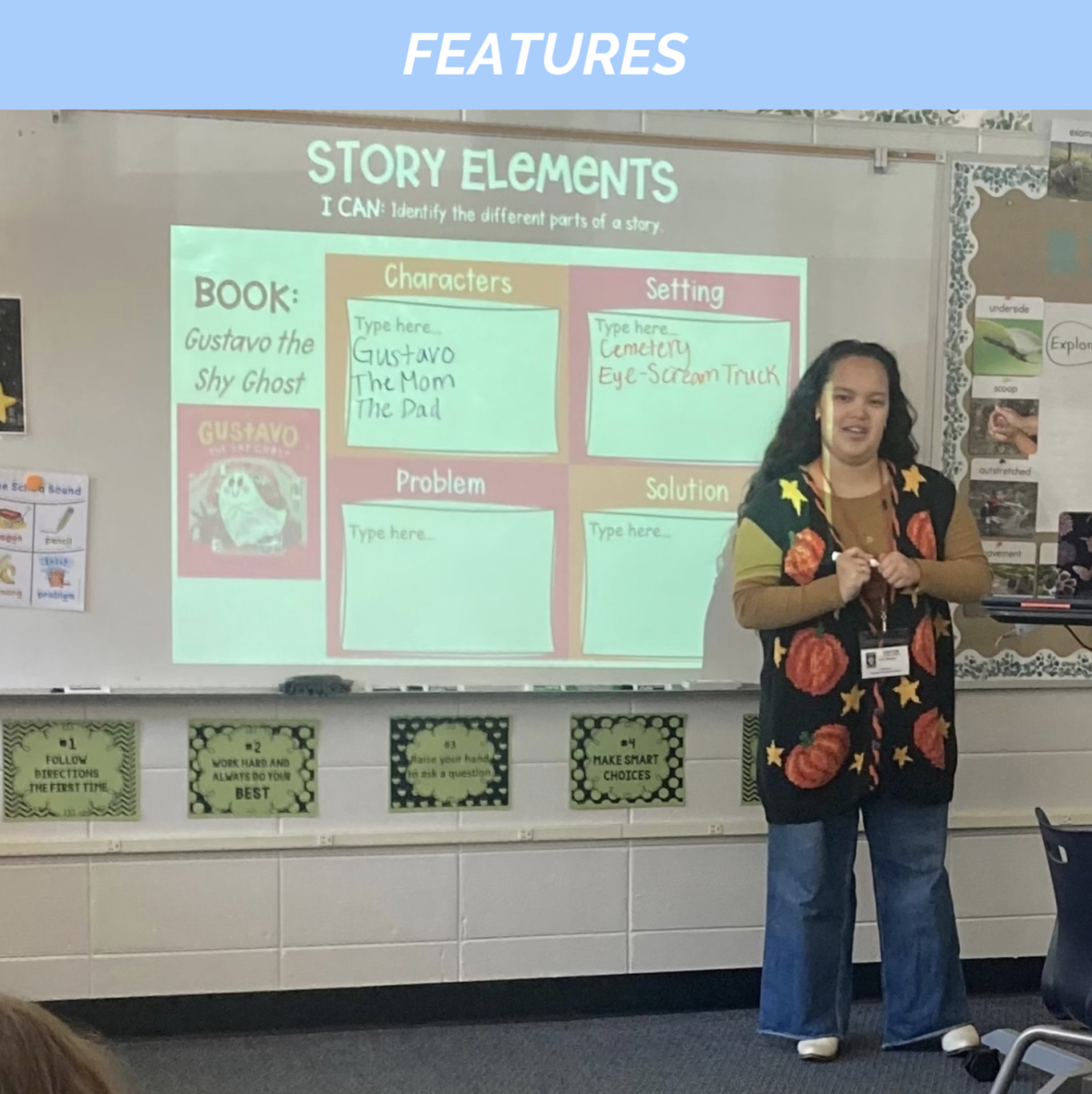

One September day, senior Amanda Ontaneda finished a triathlon.

Well, it wasn’t a triathlon, per se. But the DriTri class at Orangetheory Gym just might be the closest thing available. Preparing for a triathlon-inspired event Redditor @kaydaniel85 called “Dri Tri or Die Trying,” participants are trained to complete an indoor 2,000 meter row, 300 body-weight reps on the floor and a 5K on the treadmill – all with only a reusable water bottle and a dream. As someone who only managed a ten-minute mile after weeks of practice… let’s just say I’m getting a stitch just typing this.

But where many others (*cough* me *cough*) would just give up, Ontaneda… didn’t. She kept going, persevering until the multiple month long class was done – and emerged feeling stronger for it.

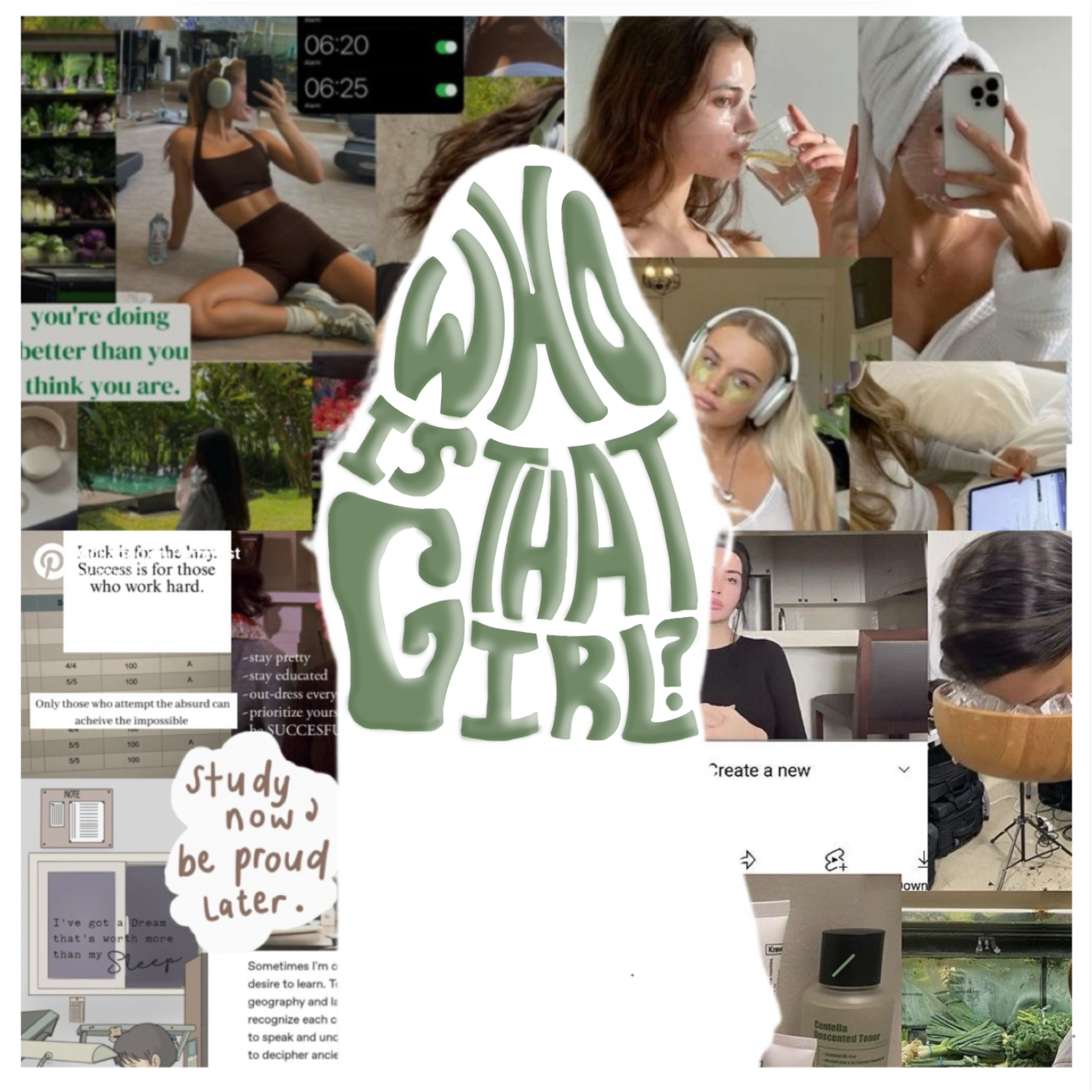

When you couple this discipline with her volleyball ELITE medallion, awe-inspiring knowledge of makeup products and the fact that she was literally a poster child for the slick-back ponytail in last year’s yearbook, it’s unsurprising one classmate called her a real-life “that girl.”

But what does “that girl” mean, really? And why should people whose biggest source of exercise is the distance from their desk to the coffeemaker care about it?

The “that girl” aesthetic emerged from the hazy fog of 2021 post-COVID confusion. TikToker @angelxadvice posted a New Year’s Resolution ideas video with a lip-syncing woman in the background, advising viewers to do things like “try and drink 2litres of water a day, you need it” and cut down screen time to a jaw-dropping one hour per day. (Yes… one hour. I’m pretty sure that’s the screen time I get from hitting the snooze button in the morning alone.)

The video in question was titled “how to be that girl in 2022.” Despite the fact that the post itself garnered a meager 569 likes — “Pathetic,” scoffed the 15-year-old writer who peaked at 108 followers — the idea of “that girl,” a successful, healthy, hydrated, fashionable and beautiful young woman, stubbornly lingered. “That girl” not only became a viral TikTok aesthetic with over 1.4 million videos, but burst through platform barriers.

It reached the recipe-loving moms on Pinterest and seven-year-old boys woefully unaware of what “Hawk Tuah” means on YouTube. It staked its flag on Instagram and Tumblr — the sites of preppy, sporty girls and the people preppy, sporty girls drive to homeschool, respectively — and though it fell short of its own popular domain on the arguably male-dominated Reddit, it’s still featured in many “asks.”

So who, exactly, is “that girl”?

Well, not “it girl,” for starters. “It girl” is a catch-all term describing any girl who’s beautiful, magnetic and popular — in fact, Dictionary.com says it originated all the way back in 1927 to describe Clara Bow. (Yes, Swifties… “Tortured Poets’ Department” Clara Bow. You can stop foaming at the mouth now.)

“That girl,” meanwhile, is different. “That girl” doesn’t settle for just being beautiful. Maybe she’s also a straight-A student or the peak of human physical fitness. Maybe she’s perfectly clear-skinned – or even a rising entrepreneur. Whatever the case, the Aesthetics Wiki’s page on “that girl” agrees on one thing: “The theme of ‘That girl’ is total mental and physical health.”

This is easy to spot in “that girl’s” recurring themes and images: academic and career success, legging-clad workouts and morning and skincare routines so meticulously regimented, they could make a military general blush.

“I’m very active in, like, weightlifting, and I’m very passionate about my health and working out,” Ontaneda said. “I inspired myself, you know, like, no one really kind of motivated me. I kind of did it myself, but it’s something I’m very proud of.”

Like many online aesthetics, “that girl” is spread through the sweat, tears and algorithmic preferential treatment of certain influencers. Ontaneda cites TikTokers Alix Earle and Tianna Robillard as her fashion and makeup inspiration, for instance. (What is it about unusual names that gets the TikTok algorithm giggling and kicking its feet? Are they more fun to draw hearts around with pink glitter gel pen or something?)

But this doesn’t only extend to real people. The academic side of “that girl” seems to prefer upholding fictional characters as paragons of the lifestyle. Rory Gilmore. Paris Geller. Hermione Granger. Even Elle Woods. All feature in “academic motivation” videos, next to pictures of perfect test scores and piles of notes. Though the “gym rat” sect is the most visible, all these #thatgirl Gilmore-themed, study motivation Pinterest collage wallpapers are impossible to ignore. (And I should know. My feed is chock-full of them.)

For example, one viral TikTok captioned “academic validation” hit a stupefying 5.1 million views for playing a Gilmore Girls clip and running “Are You Satisfied?” by MARINA in the background. “You have to sleep, it’s what keeps you pretty,” says Gilmore Girls’ Lorelai Gilmore in the video. Her daughter Rory furrows her eyebrows, surrounded by scattered papers and a coffee pot. “Who cares if I’m pretty if I fail my finals?”

And therein lies the problem. Many criticize “that girl” as glorifying unhealthily high standards and “toxic productivity culture” — what Psychology Today calls “an obsessive need to always be productive, regardless of the cost to your health, relationships, and life.” Some argue that even the aesthetic’s “relaxing” activities involve mental labor and are focused on self-improvement.

“That girl” doesn’t watch Netflix — she reads and writes in her gratitude journal. “That girl” doesn’t collapse on the couch after a hard day of work to scroll through her phone — she takes a walk with ankle weights or does Pilates in expensive Lululemon. There is no slacking off when you’re “that girl,” critics say. Every activity needs to be focused on “leveling up” into your so-called “best self.”

“When we start assigning moral weight to things like 6 a.m. wake-up calls, staying off social media, and perfect bed linens, our attention shifts from knowing what is good for us towards thinking that someone else on the internet knows better,” said The Good Trade Editorial Director Emily McGowan, who attempted to be “that girl” in her daily life. “Maybe those things are our needs, but maybe they aren’t. It makes every time we sleep in until 9 p.m. a failure and turns every missed journal opportunity into defeat. That doesn’t seem like self-care anymore.”

Still others maintain that the “that girl” aesthetic is unfair towards girls who aren’t wealthy. The women starring in “that girl” videos appear to have enough money to buy expensive items seemingly inseparable from the aesthetic, like skincare, avocados, name-brand athleisure and workout equipment. They also have the free time to meditate and prepare artfully arranged, nutritious meals, while in reality, many don’t have the financial luxury of time not spent either working or asleep.

(And by “many,” I mean me. I’m writing this at 11 o’clock at night. If I followed the “that girl” aesthetic the way critics present it, I’d be prettily snoozing in my silk bed sheets after a three hour-long night routine.)

“It’s [negative effects of ‘that girl’] definitely tied in with social media,” Ontaneda agreed. “There’s definitely, like, ‘Yes, I have higher self-esteem [from following the aesthetic],’ but there’s always going to be that self doubt that’s gonna be there and just comparing yourself to other girls that you see.”

Despite this, “that girl” is, nevertheless, an internet aesthetic — it’s not necessarily meant to be realistic, only escapist.

Escapism is what the Merriam-Webster Dictionary calls “habitual diversion of the mind to purely imaginative activity or entertainment as an escape from reality or routine.” In short, it’s pretending to live in a fake, better reality — just like Finns and the people who run our government.

Take the popular aesthetic cottagecore, for example. A quick Pinterest search reveals countless images of small country farms, flowering meadows and adorable, fluffy baby chicks. But does everyone following this aesthetic actually leave the world behind to live in a wildflower-overrun homestead? The answer is an overwhelming no.

It logically follows that people usually like cottagecore not because they actually expect to live in a cottage or believe everyone should, but because it offers a mental escape from the work-focused, modern world. “For young people, the pull of the [cottagecore] aesthetic is particularly strong; jilted by a world of rising political tensions, climate catastrophe, and economic recession, they are in search of an escape from the humdrum depression of late-stage capitalism,” writer Irma K. for Lithium Magazine aptly put it.

It could be argued that “that girl” is an opposite reaction to the same situation. While cottagecore escapism lets viewers imagine an existence outside modern life, “that girl’s” version allows viewers to imagine winning at it. When examined in the light of cottagecore, “that girl” isn’t a malicious glorification of toxic productivity, but an escapist fantasy of embracing and exceeding modern society’s expectations instead of running from them — and a fantasy its proponents are well aware is just that.

All in all, what appears to be a popular option is to keep some parts of “that girl” and leave others out. Ontaneda acknowledges that always following the aesthetic perfectly seems highly improbable, if not outright impossible.

“I’m like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to go to school.’ There’s a lot of days where I don’t put on makeup, I just throw my hair in a ponytail,” she admits. “So, yeah, like, there’s always going to be those days too.”

McGowan adopted a similar approach. She sticks to the “that girl” path by sitting in the sunlight every morning and “practicing gratitude,” but cast aside rigidly holding herself to making her bed and drinking lemon water for an audience that didn’t exist. “This is my way of being,” she ends her article with, “and I’m okay with that.”