Iranian-American Harvard student speaks out about current protests

March 8, 2023

Last semester at Harvard, Iranian-American graduate student Ciara Moezidis co-organized a “die-in” — a demonstration where people lay on the ground playing dead as a symbolic statement — in solidarity with protests in Iran. Organizers stood amongst the 60 attendees that Moezidis estimates attended, reading off the known names and ages of victims on Oct. 20.

Using the platform of her university as a jumping off point, Moezidis knew she had to use the privilege she had to speak up about the issue.

“As long as people in Iran are protesting and fighting for these freedoms, then I need to do my job,” Moezidis said. “Being a member of the Iranian diaspora, [it felt crucial] to uplift their voices and support the movement in whatever way I can.”

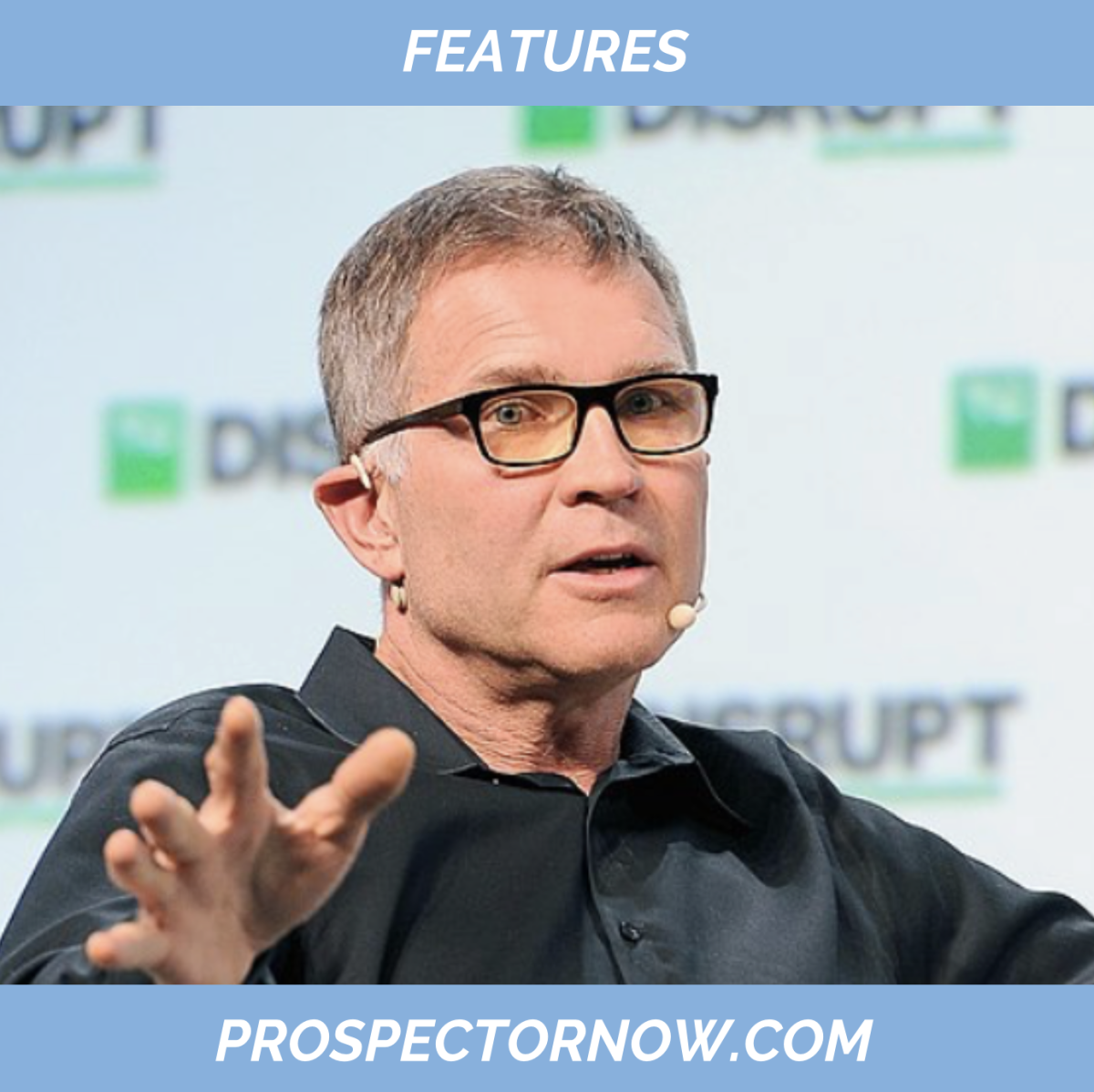

Moezidis, who is both a friend to World Religions teacher John Camardella and a dual master’s candidate at Harvard Divinity School and The Fletcher School at Tufts University , was not the only one mobilizing in response to this issue.

In fact, this demonstration at Harvard is one of hundreds that span from Iran to around the globe: according to Euro News, in Stockholm, Sweden, women have hacked off their hair in solidarity; on Nov. 21, the Iranian football team refused to sing their national anthem at the World Cup in Qatar, and fans chanted slogans against the regime outside the stadium; and, within small towns and cities alike, women-led movements, chanting ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ as they unite under one voice to speak out against the regime. (SEE “Facing Forward” in Issue 5 of the Prospector for more details about the current protests)

Moezidis herself has made it her mission to encourage both education and change of the happenings in Iran through hosting events, panels and protests.

Additionally, Moezidis uses social media to amplify this message; her video of the “die-in” demonstration, for example, gained over 100,000 views, many of whom were based in Iran.

“It’s a way to continue to show that even though all of this stuff is happening, we still are watching and paying attention,” Moezidis said. “We’re supporting where we can.”

Using social media, Moezidis says, shows protestors in Iran that they are backed by a larger global community. This is especially important due to the Iranian government’s strong crackdown on internet access, which Moezidis says only goes to show the power that social media can have.

While there wasn’t a total internet shutdown, internet blackouts — including difficulties accessing WhatsApp, Instagram and mobile networks — were confirmed by both Meta and internet watchdog Netblocks. Furthermore, the lack of international journalists on the ground has contributed to minimal coverage of the happenings in Iran.

The goal of the Iranian government is to make it really difficult to know of all the human rights violations happening in Iran, according to Moezidis. Early on, if people outside the country weren’t actively following Middle Eastern current events, it’s very possible that the confines of algorithms casted blinders to what was occurring. Many of Moezidis’ friends, for example, would not have known about the protests if she herself had not unearthed it as a conversation topic in September.

Due to her heritage and the need to follow Iranian current events closely for her studies, Moezidis heard about the protests within the first week of Mahsa Jina Amini’s death.

Using her privilege and positionality, she began sharing the news on social media; however, Moezidis found that while people were really open to hearing about the issue, due to a longstanding pattern of Middle Eastern news not being very nuanced — meaning it often creates more questions than answers — she, as an Iranian-American, had to contextualize what was happening in the country for others.

“It’s really important for non-Iranians to know about this and speak up because there are a lot of ramifications in terms of … Iranians in the diaspora do not want to put their [own] families in harm’s way,” Moezidis said. “Many of my Iranian-American friends are scared to talk about it because they do not want to risk losing their chances of going back to Iran.

When she first began posting on social media about the protests, Moezidis had a conversation with her family about the possible ramifications of speaking out: namely, not being able to visit Iran again.

“I was lucky, in a way, that my family decided that this cause was bigger than their ability to go back to Iran,” Moezidis said. “Then I took it upon myself, ‘OK, I feel even more responsible to uplift these voices publicly because others don’t have that luxury.’”

Moezidis says that months after the protests first began, members of the Iranian diaspora specifically have played a large role in keeping Iran in the mainstream news circles.

Using both the forces of legislation and spreading awareness through social media in tandem, Moezidis believes that everyone can and should get involved in the cause. Whether it’s through educating or advocating, she stresses that teenagers have voices that need to be heard, too.

“I think that it can be really important to just be engaged,” she said. “Be aware, beyond our own bubbles. Given this is one of the first and largest women-led revolutions basically in history, it’s really important to continue to uplift women in the U.S., but also abroad. Ultimately, it’s the same struggle.”